This tutorial article is going to show you how to create a Linux virtual machine from a physical Linux system. These instructions are generic enough to work with any Linux distribution, such as Ubuntu, Fedora, Red Hat, CentOS, Debian, Mint, etc.

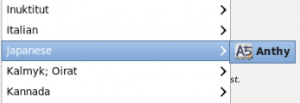

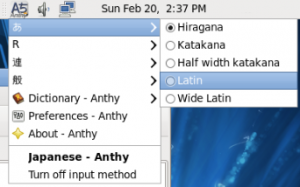

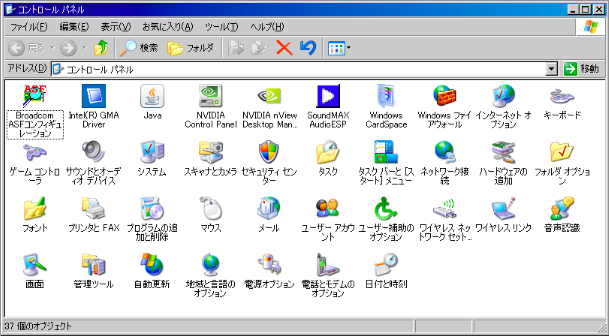

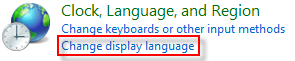

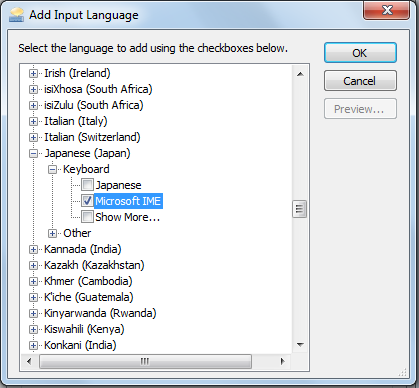

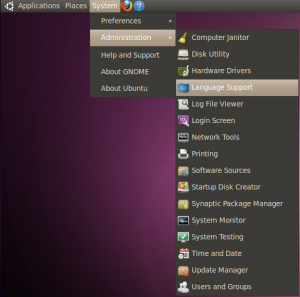

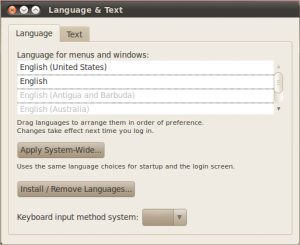

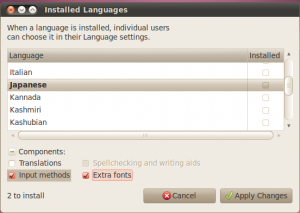

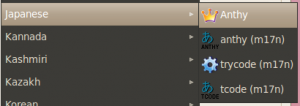

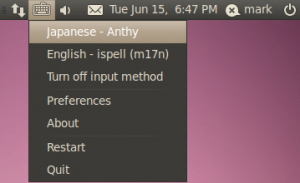

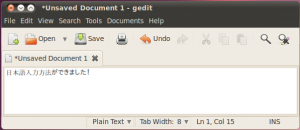

There are many reasons why you would create a VM of a physical system you have running. You might want to test out things before you try them on your actual system. It is useful when you are translating to have both the English and Japanese (or other language) OS and applications open side by side to reference the correct translations easily. Whatever the reason, this article will show you one way to do it pretty easily.

Overview of the Linux VM creation task:

Tools and Resources Needed

- SystemRescueCd ISO file

- Blank CD-ROM or USB disk

- USB disk drive large enough to fit entire Linux system

- VMware or VirtualBox

Preparation Tasks

- Make note of the disk partitioning

- Create a bootable Linux rescue disk

Main Tasks

- Image the hard drive partitions

- Create an empty Virtual Machine

- Recreate the hard drive partitions

- Restore the hard drive partitions

- Set up the boot loader

Final Task – Boot the VM

Optional Task – Configure X11

Preparation Tasks

Make Note of the Disk Partitioning

On the physical Linux system we want to virualize, run the df command to list the partitions and mount points

df -h

Make a note of the partitions, their sizes, and mount points. You will use this information later to recreate the disk partitioning in the virtual machine.

Create a Bootable Linux Rescue Disk

For the task of converting a physical Linux system to a virtual machine we are going to use another version of Linux to do the work in. Any bootable version of Linux will work, and I really like SystemRescueCd for this task. It is a light-weight Linux system that comes with all the system tools you’ll need for this job like partimage and fdisk (or GParted).

Download the SystemRescueCd ISO file.

Burn the ISO file to a CD-ROM, or follow the instructions to make a bootable USB stick.

Power down the physical Linux computer we are going to virtualize and put the SystemRescueCd in the CD-ROM drive or USB drive.

Turn the computer on and boot to SystemRescueCd Linux.

Main Tasks

Image the Hard Drive Partitions

Plug in your external USB hard drive.

Run the dmesg command to find the device name of the USB hard drive.

dmesg

Look for your hard drive name and description. For example, if you plugged in a Western Digital My Passport drive you should see something similar to this:

usb 2-1: Product: My Passport 070A usb 2-1: Manufacturer: Western Digital sd 4:0:0:0: [sdb] 1463775232 512-byte logical blocks: (749 GB/697 GiB) sd 4:0:0:0: [sdb] Write Protect is off sd 4:0:0:0: [sdb] Mode Sense: 23 00 10 00 sd 4:0:0:0: [sdb] Assuming drive cache: write through sdb: sdb1

The key piece of information here is the sdb1 on the last line. This is the device name we will use to mount the USB hard drive.

Create a directory to mount the USB hard drive. For example, a new directory called flash.

mkdir /mnt/flash

Mount the USB hard drive, device sdb1, on the newly created directory.

mount /dev/sdb1 /mnt/flash

Run the partimage program to image the partitions.

partimage

Use the GUI to select the partition to image.

Press Tab and enter the file name for the partition. For example (Assuming the partitions are on device sda):

/mnt/flash/sda1.partimage.gz

Press F5 twice to navigate to the next screens and press OK to start the imaging process.

Repeat this process for each partition on the Linux system. Make sure to name the files appropriately.

Note: Partimage will also show the partitions of the USB drive you mounted. Do not image the partitions of your USB disk. Also, do not image any extended or swap partitions.

When you are finished imaging all of the disk partitions, unmount the USB disk drive.

umount /mnt/flash

Shut down SystemRescueCd and restart your Linux system.

reboot

Create an Empty Virtual Machine

Create a new VM in VMware (or VirtualBox).

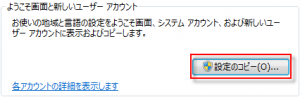

Configure the VM to have similar hardware specifications as the physical Linux computer: RAM, processor, hard disk. It is important that the hard disk be the same size or larger than the physical machine so the partitions fit.

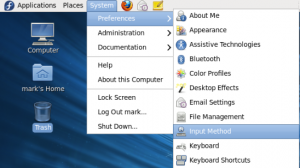

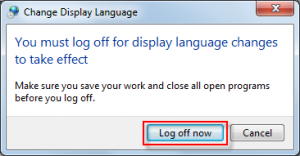

Set the VM to boot from the CD-ROM drive using the SystemRescueCd ISO file.

Boot the empty virtual machine into SystemRescueCd.

Recreate the Hard Drive Partitions

Run the fdisk command to find the hard drive device.

fdisk -l /dev/sda

If it is sda and your drive was around 100 GB, you will see something like this:

Disk /dev/sda: 105.2 GB, 105226698752 bytes

Use fdisk to recreate the disk partitions of the original physical Linux computer. You should have made note of these in the preparation tasks. fdisk is a command line program to partition the drive. (You can also use the GUI GParted program in X Windows if you prefer. Press startx and select GParted from the menu.)

fdisk /dev/sda

Press n to add new partitions.

Press a to toggle the bootable partition (the /boot partition).

Press t to toggle the swap partition by setting it to 82.

Press w to write changes to disk.

Press m at any time for a list of options.

Restore the Hard Drive Partitions

Plug in your external USB hard drive and connect it to the virtual machine.

Run the dmesg command to find the device name of the USB hard drive.

dmesg

Look for your hard drive name and description.

Create a directory to mount the USB hard drive. For example, a new directory called flash.

mkdir /mnt/flash

Mount the USB hard drive, for example device sdb1, on the newly created directory.

mount /dev/sdb1 /mnt/flash

Run the partimage program to restore the partitions.

partimage

Use the GUI to select the partition to restore.

Press Tab and enter the file name and location for the image file. For example:

/mnt/flash/sda1.partimage.gz

Press Tab and change the Action to be done to Restore partition from an image file.

Press F5 twice to navigate to the next screens and press OK to start the restore image process. In VMware you will probably have to press Function F5 to get the F5 key to work.

Repeat this process for each partition on the Linux system.

When you are finished imaging all of the disk partitions, unmount the USB disk drive.

umount /mnt/flash

Set Up the Boot Loader

The final step is to set up the boot loader and install it into the master boot record.

Mount the boot directory. For example, if sda1 is the boot partition and sda3 is the root partition.

mkdir /mnt/root mount /dev/sda3 /mnt/root mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/root/boot

Verify the configuration of the boot configuration file. Assuming you are using GRUB:

nano /mnt/root/boot/grub/device.map

Nano is a Linux text editor. You can also use pico or vi.

You want to verify that the device in the configuration file matches what it is in the VM. For example, if it says this:

(hd0) /dev/hda

You may need to change hda to sda. In this example we need to change it.

(hd0) /dev/sda

Exit Nano or whatever text editor you used.

Run grub-install to install GRUB into the MBR.

grub-install --root-directory=/mnt/root /dev/sda

Final Tasks

We’re all done. Now reboot in SystemRescueCd and your virtual machine should now boot into the same Linux setup that is on your physical machine.

reboot

This VM is now an exact copy of the physical Linux computer. You have successfully done a P2V (Physical to Virtual) conversion of your Linux system.

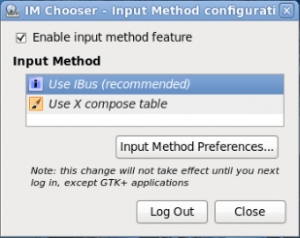

Optional Task – Configure X11

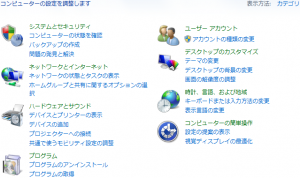

Depending on the version of Linux you are using, it may not be able to use the VMware settings to display X Windows properly. In that case, you will need to make a simple change to the X11Config file.

First, make a backup of the X11Config file. This assumes it is located in /etc/X11.

cp /etc/X11/XF86Config /etc/X11/XF86Config.backup2

Edit the X11Config file.

nano /etc/X11/XF86Config

Change the Driver and BoardName settings in the Device section from the VMware settings to a generic Vesa setting.

Section "Device" Identifier "Videocard0" Driver "vesa" VendorName "Videocard vendor" BoardName "VESA driver (generic)"

Save the file and restart. You should be able to get X Windows to start now.

That’s it. It looks like a lot of steps, but it is not that difficult to do. The longest part is imaging and restoring the partitions.

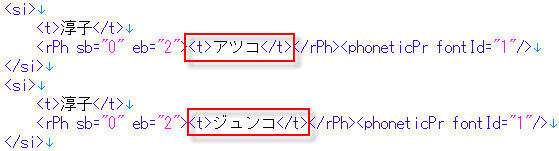

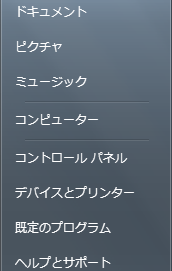

Now that you have a virtual version of your Linux computer, you are able to do unique things like snapshots and work with multiple configurations or languages at the same time. This is really helpful when translating software from one language to another because you can now have both language versions running at the same time on the same desktop.